Banking Deserts in Los Angeles

Across Los Angeles County, more than half a million residents lack access to a single bank or credit union within their neighborhoods. For these Angelenos living in a banking desert – an area that lacks sufficient access to financial institutions – this means that they cannot easily deposit a paycheck, take out a loan for a new car, or even write a check to pay for everyday household expenses.

A survey by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) of unbanked households found that 57 percent of unbanked households cited “do not have enough money to keep in an account” as a reason for not banking. Nearly 11% cited “do not trust banks” and almost 10% cited “bank fees are too high” as the main reasons for not banking.

The Cost of Going Unbanked

Traditional banking services have historically provided the basic financial building blocks for individuals and families to gain economic stability. Residents without access to banking services often do not have a savings account to save for their future. They are unable to access affordable credit to purchase a home, pay for higher education, or replace an older vehicle.

Further, when residents lack access to banking services they often turn to payday loans, check-cashing services, auto title loans, and other non-traditional forms of credit that charge high-interest rates and expensive fees, trapping consumers in a dangerous cycle of debt.

According to a report by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, more than 80% of payday loans are rolled over or followed by a new loan within 14 days.

A study by the Brookings Institute calculated that a full-time worker’s reliance on check cashing could cost more than $40,000 over their lifetime. Hard-working residents could save thousands of dollars over their careers if they had access to low-cost checking and savings accounts provided by traditional financial institutions. The same study also found that if workers had access to financial advisors and investment tools, they could generate $360,000 over a forty-year career.

For low-income residents in Los Angeles County, the costs of going unbanked only exacerbate an already precarious financial reality. Take, as an example, a 24-year-old resident in Green Meadows that earns the annual median household income of $33,626, which after taxes averages approximately $27,000. The median rent in Green Meadows is $1,080 per month, which leaves little discretionary income after paying for food, healthcare, transportation, and education or job-related expenses.

Because Green Meadows lacks even one bank or credit union within the neighborhood, this resident will spend approximately $750 a year to cash a bi-weekly paycheck at a local check cashing location with a 2.75% fee. To take this a step further, if he invested the amount spent on check cashing in a retirement account with a 7% annual return, this resident would earn almost $200,000 by the time he retires at 67.

Which Neighborhoods are Affected and Why?

Nearly one in five neighborhoods in Los Angeles County does not have a single financial institution such as a bank or credit union.

Nearly 600,000 residents in 46 neighborhoods across LA County do not have access to a single bank or credit union. Click below to explore how many banks and credit unions are in your neighborhood:

High-poverty neighborhoods are disproportionately affected by the lack of financial institutions. Out of the five most populous neighborhoods without a single financial institution – Central-Alameda, Green Meadows, Westmont, and Willowbrook – four are located in South Los Angeles and report significantly lower median household incomes than the County median of $56,196. These neighborhoods have an aggregated median household income of $32,295 and are predominantly Black and Latino.

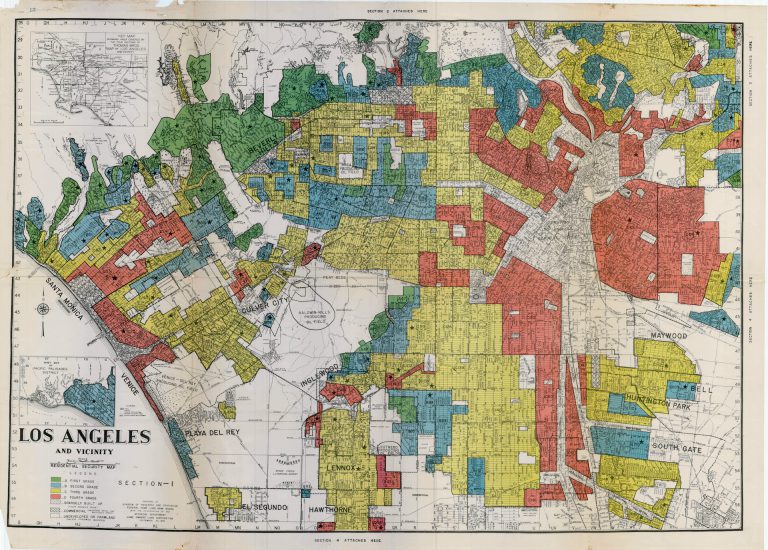

Diverse, low-income communities have historically been excluded from financial services through a practice of financial exclusion known as redlining, which describes the practice of grading neighborhoods based on their credit risk by the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC). In order to support the issuance of new homeownership loans, the HOLC created a series of maps that ranked neighborhoods by risk. Wealthy, predominately white neighborhoods were outlined in green, reflecting low risk neighborhoods. Low-income, ethnically diverse neighborhoods such as Boyle Heights and Central-Alameda in East and South Los Angeles were outlined in red, reflecting high risk neighborhoods. Redlining quickly became known later as de facto segregation and prevented these communities from accessing credit and formal financial institutions. While redlining was outlawed in 1968 by the Fair Housing Act, the effects of this discriminatory practice lasted generations and continues to impact the financial stability of many low-income communities across the nation.

The Future of Community Investment

Despite the alarming number of LA County communities that lack access to banks and credit unions, important steps are being taken to bring investment into low-income communities. Private philanthropic dollars such as the California Endowment’s Building Healthy Communities program and innovative federal programs such as the Promise Zone initiative are helping to bring new investments into traditionally under resourced communities.

Further, banks are incentivized to invest in low – and moderate-income communities through the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), which annually brings more than $100 billion in capital to communities across the country.

“The CRA’s impact to low and moderate income individuals has resulted in more affordable housing, economic development, neighborhood revitalization, greater support for community development organizations, and an increase in lending to underserved segments of local economies and populations,” said Tom Lillig, Vice President of Community Reinvestment for Bank of the West.

While these activities provide some economic opportunity for under-served populations, more is needed to ensure that all LA County communities, regardless of income levels or location, have access to traditional banking practices. By identifying the neighborhoods most in need of financial institutions, neighborhood data can help us better advocate for improved financial opportunity for all Angelenos.

Juan Lopez

Juan Lopez is a first-generation American, a proud product of public schools and the first in his family to graduate college. Juan is currently pursuing a Masters in Public Administration at the University of Southern California Price School of Public Policy. He attended Long Beach City College and transferred to the University of Oregon where he graduated with a BA in Political Science. He most recently served as Director of Technology and Innovation in the Office of Los Angeles City Controller Ron Galperin. As a forward-thinking public servant, Juan focused on cutting red-tape, making government more efficient and making a meaningful difference in the lives of Angelenos. Juan loves hiking, writing, breakfast burritos and road trips.

Sources

“2015 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.” EconomicInclusion.gov, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, www.economicinclusion.gov/.

“Community Reinvestment Act.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2017, www.frbsf.org/community-development/initiatives/community-reinvestment-act/.

Fellowes, Matt, and Mia Mabanta. “Banking on Wealth: America’s New Retail Banking Infrastructure and Its Wealth-Building Potential.” Brookings, Brookings, 28 July 2016, www.brookings.edu/research/banking-on-wealth-americas-new-retail-banking-infrastructure-and-its-wealth-building-potential/.

Reft, Ryan. “Segregation in the City of Angels: A 1939 Map of Housing Inequality in L.A.” KCET, KCET, 14 Sept. 2017, www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/segregation-in-the-city-of-angels-a-1939-map-of-housing-inequality-in-la#_ftnref14.

Burhouse, Susan, et al. “Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.”Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation,” Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Oct. 2016. www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2015/2015execsumm.pdf.

Yun, Alyssa. “Financial Exclusion: Why It Is More Expensive to Be Poor.” Penn Wharton Public Policy Initiative,

Penn Wharton Public Policy Initiative, 2 June 2017, publicpolicy.wharton.upenn.edu/live/news/1895-financial-exclusion-why-it-is-more-expensive-to-be/for-students/blog/news.php#_edn1.

Burke, Kathleen, et al. “Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.”Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Mar. 2014. files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201403_cfpb_report_payday-lending.pdf.

Photo Attributions

Cover Photo: Photo courtesy of Istock/RiverNorthPhotography

Photo 1: Photo courtesy of Istock/EHStock

Photo 2: Photo courtesy of Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al., “Mapping Inequality,” American Panorama, ed.

Photo 3: Photo courtesy of Istock/vm

Photo 4: Photo courtesy of Istock/NanoStockk

Photo 5: Photo courtesy of Istock/assalve

Photo 6: Photo courtesy of Istock/YuriArcurs